DEMOCRACY

Female Candidates Running In Record Numbers For The Midterms — Just Not In California

The midterm elections are widely expected to usher in this century’s “year of the woman” – an explosion of women entering government.

Massachusetts will likely elect its first black woman to Congress, Arizona is poised to send its first woman to the U.S. Senate, and fully 50 percent of Democratic congressional nominees this year are women.

But California – a policy trendsetter that in 1993 became the first state to be represented simultaneously by two women in the U.S. Senate – won’t be making history this year when it comes to women.

All of California’s 53 House seats are on the ballot, and a record 57 women entered the primaries. But the Golden State’s midterm election contests skew very male.

Since none of the 39 Democratic representatives are facing a serious challenge, Democrats hoping to take back the House of Representatives are targeting California’s 14 Republican-held congressional districts – particularly the seven that favored Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

Of 10 total battleground districts in California, only three Democratic challengers are women.

I’ve been covering congressional races since 2004, first as a national political journalist in Washington and most recently leading California coverage at the Los Angeles Times. Now, as director of the Annenberg Media Center at the University of Southern California, I help journalism students tell stories about the midterms.

There’s not much to share with these up-and-coming reporters about California’s role in 2018’s year of the woman: Nearly all the female newcomers in Washington next year will win office in other states.

California’s female candidates

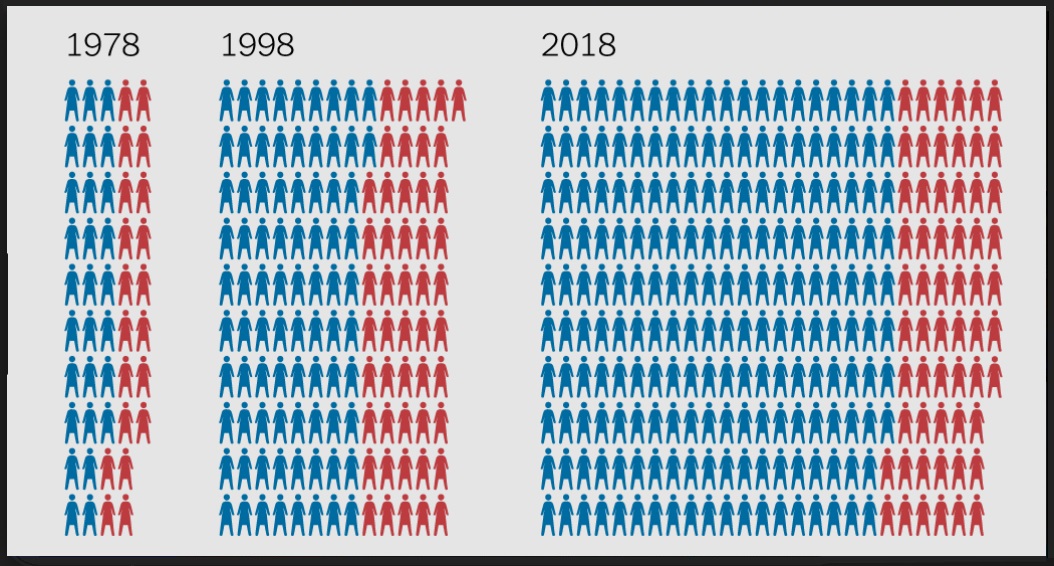

Women represent roughly half of the country but make up just 20 percent in Congress. More female lawmakers would better align the U.S. government with the nation’s demographics. And, research suggests, it might just lead to more compromise and better policy.

In the absolute best-case scenario for Democrats – one in which all its female challengers defeat Republican incumbents – three new women from California could be headed to Congress in January.

Gaining three women would simply bring California’s Democratic delegation up to 19 total women in Congress – the same number it had back in 2016. That year, several female lawmakers – including some who won office in 1992, the original “year of the woman” – retired.

But it would leave California Republicans without women in Congress because a Democratic sweep would mean the defeat of Mimi Walters, the state’s only female GOP representative. Her Democratic challenger for the Orange County-based 45th District, law professor Katie Porter, has a 64.4 percent chance of winning, according to the FiveThirtyEight rankings.

Female democrats are running against male Republicans in only two battleground districts.

First-time candidate Katie Hill is running in the 25th District, which includes parts of Los Angeles and Ventura counties. She has a better chance of winning than other female challengers. Thirty-one-year-old Hill, a millennial with a rock-climbing hobby, is challenging Rep. Steve Knight, the last elected Republican in Los Angeles County.

She has a 71.8 percent chance of ousting Knight, according to the analysts at FiveThirtyEight.

There’s a slim chance Democrat Jessica Morse could topple Rep. Tom McClintock in the northern suburbs of Sacramento. But it’s really slim: Trump won McClintock’s 4th Congressional District by 14 points in 2016.

In the final days of the campaign, California Democrats are putting some minimal effort into Audrey Denney’s attempt to unseat Rep. Doug LaMalfa in a far northern California congressional district that favored Trump by nearly 20 points.

Male Dems vs. female GOP

In California’s two most competitive midterm races, the Democratic hopeful is male and the Republican candidate is female.

Republican Darrell Issa, who represents northern San Diego and parts of Orange County in the 49th Congressional District, barely managed to get re-elected for a ninth term in 2016. He won by less than 1 percent, the slimmest margin of any race in the country that year.

Now that Issa is retiring, the 49th represents the Democrats’ most promising opportunity to capture a California seat from Republicans.

To do so, Democrat Mike Levin – the favored candidate – must defeat Diane Harkey, the Republican chairwoman of the state Board of Equalization. Her campaign has struggled in recent weeks. That’s good for Democrats but not for California raising its female representation in Congress.

Democrats are also optimistic about the 39th District, where Republican Rep. Ed Royce is retiring after 26 years in Congress. Clinton won this majority-minority district – where most residents are people of color – by 8 points in 2016.

There, the Republican former state Assemblywoman Young Kim is locked in a toss-up battle with Gil Cisneros, a Latino Democratic philanthropist best known for winning the lottery. While the #MeToo movement has shifted political fates in other states, a sexual harassment accusation that could have hurt his campaign was later recanted.

Women in power

California’s other competitive congressional races feature two male candidates.

Its next governor will also be a man – either Republican John Cox or Democrat Gavin Newsom. A woman has never run California.

It has, however, had two female senators for decades. This year Sen. Dianne Feinstein will almost certainly be re-elected, rejoining Sen. Kamala Harris.

Anyone lamenting California’s underwhelming pink wave in 2018 can take solace in another fact, too: Nancy Pelosi, the longtime representative from San Francisco, is likely to remain the highest-ranking Democrat in Washington.

The only question is whether her title will be minority leader or a title she held once before: speaker of the House.

Christina Bellantoni, Professor of Professional Practice and Director of the Media Center, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()