EQUALITY

Criticism Of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Clothes Echoes Attacks Against Early Female Labor Activists

As the youngest woman ever elected to Congress, 29-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has attracted much media attention.

A young outspoken woman who defines herself as “an educator, an organizer, a working-class New Yorker,” Ocasio-Cortez has positioned herself as an outsider who isn’t afraid of speaking truth to power.

While her radical political positions – from abolishing ICE to Medicare for all – is responsible for some of that publicity, her fashion choices have also drawn a lot of scrutiny.

“I’ll tell you something,” Washington Examiner reporter Eddie Scarry tweeted on Nov. 16, “that jacket and coat don’t look like a girl who struggles.”

It seems that some critics just can’t accept the fact that an unapologetic Democratic socialist like Ocasio-Cortez – who calls for a more equal distribution of wealth and fair shake to workers – can also wear designer clothes.

To a historian like me who writes about fashion and politics, the attention to Ocasio-Cortez’s clothing as a way to criticize her politics is an all-too-familiar line of attack.

Ocasio-Cortez isn’t the first woman or even the first outsider to receive such treatment.

In particular, I’m reminded of Clara Lemlich, a young radical socialist who used fashion as a form of empowerment while she fought for workers’ rights.

Lemlich – like Ocasio-Cortez – wasn’t afraid to take on big business while wearing fancy clothes.

‘We like new hats’

In 1909, when she was only 23 years old, Lemlich defied the male union leadership whom she saw as too hesitant and out of touch.

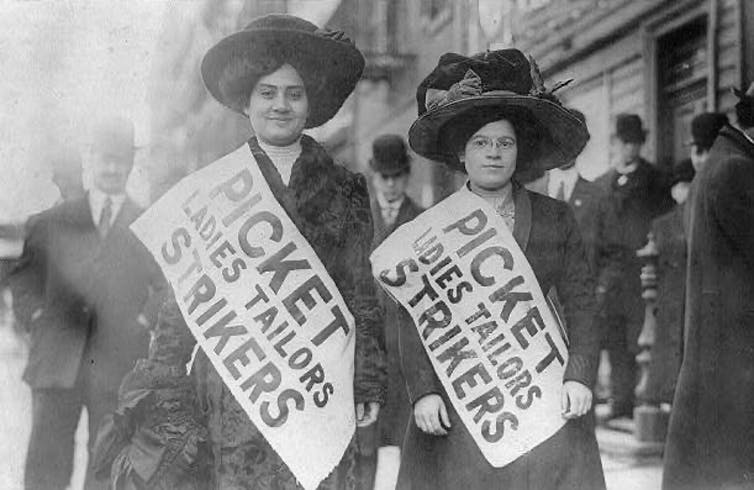

In what would come to be known as the “Uprising of the 20,000,” Lemlich led thousands of garment workers – the majority of them young women – to walk out from their workplace and go on a strike.

That 14-week strike between November 1909 and February 1910 was the largest strike by women to date, turning what was thought of as a disorganized workforce into a united, political force.

Kheel Center/flickr, CC BY

Strikers demanded better wages, hours and working conditions. But they also called to end the pervasive sexual harassment in the shops, safer workrooms, and for dressing rooms with mirrors and hooks on the walls, so workers could protect their elegant clothes during the workday.

“We like new hats as well as other young women. Why shouldn’t we?” argued Lemlich, justifying strikers’ demands. And when they went out to the streets, strikers were also wearing those nice clothes of theirs, updated according to the latest trends.

As historian Nan Enstad has shown, insisting on their right to maintain a fashionable appearance was not a frivolous pursuit of poor women living beyond their means. It was an important political strategy in strikers’ struggle to gain rights and respect as women, workers and Americans.

Library of Congress

When they picketed the streets wearing their best clothes, strikers challenged the image of the “deserving poor” that depicted female workers as helpless victims deserving of mercy.

Wearing a fancy dress or a hat signaled their economic independence and their respectability as ladies. But it also spoke to their right to be taken seriously and to have their voices heard.

Activism and fashion can work together

The strikers’ fashionable appearance was heavily criticized by middle-class observers and the male union leadership. To them, it was evidence that these women weren’t really struggling as much as they claimed to be.

Sarah Comstock, a reporter for Collier’s magazine, commented that “I had come to observe the Crisis of Social Condition; but apparently this was a Festive Occasion,” pointing to the fact that the strikers’ clothes made them look like they didn’t have any real grievances.

“Lingerie waists were elaborate, pufftowered,” she observed. “There were picture turbans and di’mont pendants.”

The New York Sun also mocked the strikers, calling them the “unwonted leisure class…all dressed in holiday attire” and showing no evidence of harsh treatment.

To critics like Comstock and the New York Sun, the fact that strikers aspired for better working conditions that would allow them to go beyond mere survival – and would provide them with disposable income to spend their wages as they saw fit – wasn’t a privilege that working-class women should have.

Despite the criticism, Lemlich and her fellow strikers were able to win concessions from factory owners for most of their demands. They also turned Local 25 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union into one of the most influential labor unions in the country, changing for the better the lives of millions of workers like themselves.

But more importantly, Lemlich and her colleagues changed the perception of what politically radical women should look like. They demonstrated that socialism and labor struggles were not in opposition to fashionable appearances.

Today, their legacy is embodied in Ocasio-Cortez’s message. In fact, if Clara Lemlich were alive today, she would probably smile at Ocasio-Cortez’s response to her critics.

The reason some journalists “can’t help but obsess about my clothes [and] rent,” she tweeted, is because “women like me aren’t supposed to run for office – or win.”

Ocasio-Cortez has already begun to fashion an image for women who, as her worn-out campaign shoes can attest, not only know how to “talk the talk,” but can also “walk the walk.”

Rachel Getman/Cornell Costume & Textile Collection

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, Visiting Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()