NEWS

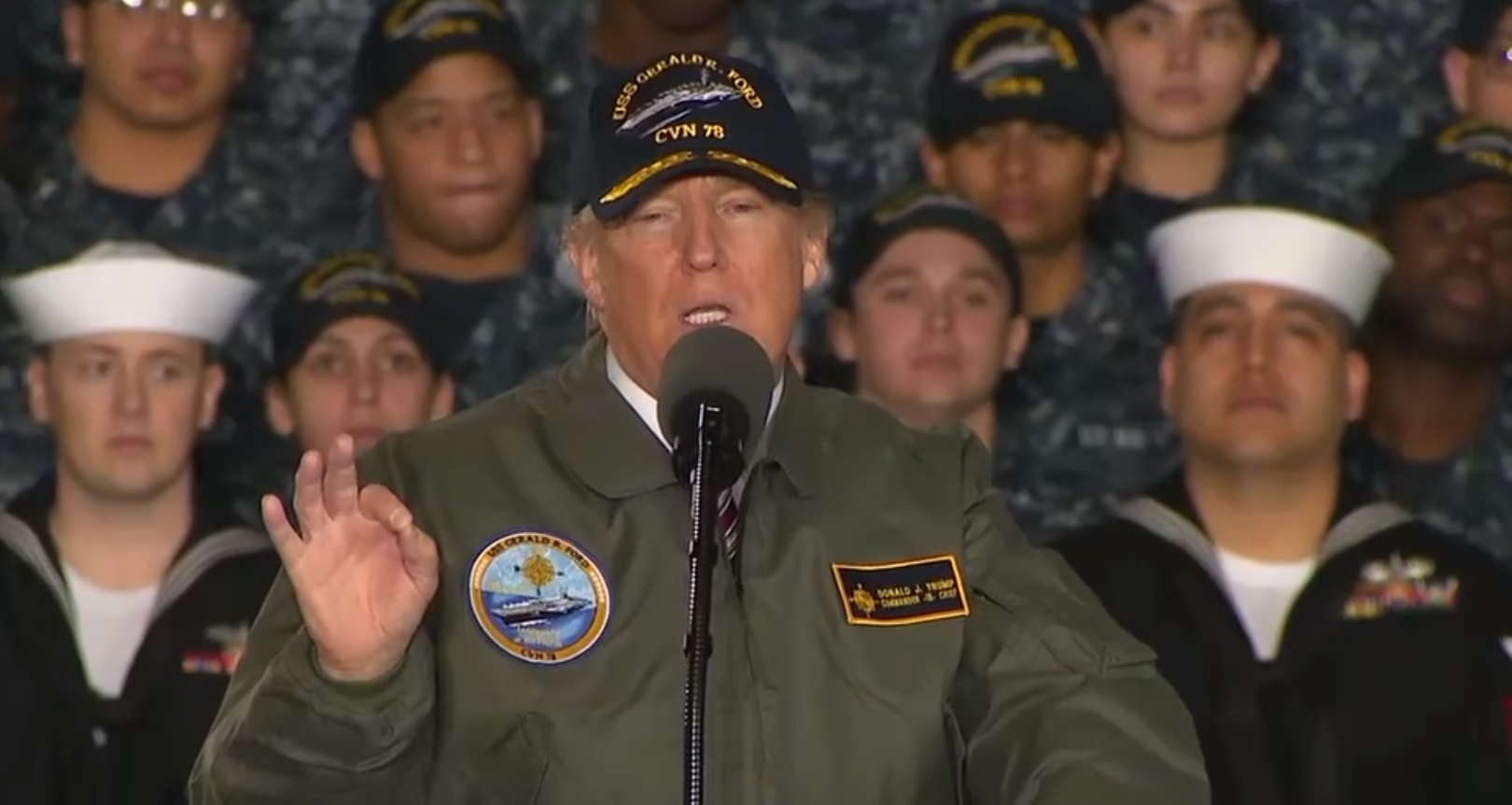

It Turns Out Trump Is Not ‘So Good At The Military Your Head Will Spin’

The US is committing 4,000 new soldiers to Afghanistan, and President Donald Trump did not even bother to own the decision himself. The Pentagon released a report about the troop surge while Trump tweeted about Hillary Clinton. This is troubling because of Trump’s lifelong habit of not taking responsibility for the failures throughout his business career. He will no doubt blame the military if something goes wrong, like he did after the controversial Yemen raid in February when Trump blamed President Obama and “the generals” for the botched operation.

It would be nice if Trump had more respect for the significance of civilian control of the military that this nation has protected institutionally for its entire existence, especially since throughout his presidential campaign Trump peppered his stump speeches with ridiculously grandiose promises that no one was better at the military than him. Of course, why wouldn’t a real estate mogul and television host of a gameshow who inherited hundreds of millions of dollars and spent years leaking made up details of his playboy life to reporters have also on the side internalized tens of thousands of pages of military doctrine for each branch of the military, and independently honed the war fighting strategies of centuries of military history that the United States’ career generals and admirals have spent decades mastering?

But on the other hand it is difficult to imagine how Donald Trump being hands-off of military matters is a bad thing, especially since it has been reported that intelligence community members fear that he does not grasp the intricacies of the information they give him if he even reads the daily security briefings he receives at all.

Fortunately, the Department of Defense is much more careful and thoughtful than Americans might believe, and while Trump repeatedly used the Iraq War during the campaign as an example of why he might know more than America’s generals about military matters (while lying about his own opposition to the war) it is appropriate to remember that the Department of Defense was originally opposed to President George W. Bush’s Iraq War before the Bush Administration ignored or shifted top-ranking generals until they found military brass who would agree to lead the mission.

Nonetheless, the decision to amplify America’s presence in Afghanistan is unsettling because the US has failed at stabilizing the country for the last 16 years. So much so that Afghanistan is the longest war in American history. Yet in an awful catch-22, an effort to walk away from stabilizing Afghanistan would sabotage US security and national interests. The struggle America faces is to provide adequate stability with minimal but still present military involvement in order to help give a centralized government control over the country and ensure the stability needed to reignite the economic activity that can raise the Afghan standard of living.

Unfortunately for American efforts against the Taliban, there is essentially no solution. Signing some deal with the Taliban would largely negate the entire purpose of the war, and national Afghan popular opinion is against the Taliban after years of oppressive rule and terror attacks. Furthermore, the country has 14 major ethnic groups recognized by the Afghan constitution, and as has been seen throughout the past 16 years, many of these groups care more for tribal ties than the capital Kabul’s attempts at federal cohesion. Additionally, the US-supported national government and its military have largely failed to stabilize the country against Taliban fighters.

This puts the US in a tight spot politically. America clearly has a political and ethical responsibility to ensure that some form of domestic centralized Afghan government can take care of itself before the US withdrawals completely, and the US cannot simply risk looking the other way as Afghanistan again becomes a safe haven for terror attacks against the West and America. In terms of moral responsibility, the US has some obligation to protect the people of Afghanistan from the Taliban and other terror groups that would love to take advantage of the power vacuum left in America’s absence, yet the US does not have the domestic political will to occupy or nation-build indefinitely.

The same American catch-22 lies in Syria and Iraq as well. Islamic terrorism has taken root in both, and the US can neither occupy them nor wash its hands of them. Including Afghanistan, these three Middle Eastern countries have tens of millions of citizens whose sovereign control has been eroded, and the nation-states have been fundamentally obliterated with vast swaths of relatively independent territories governed by groups much of the rest of the world deems illegitimate or criminal. National institutions and even basic components of governance have been dismantled, and with them much of the hope for political stabilization and economic development. Vital infrastructure has been destroyed after years of sectarian violence, which also fuels a crippling unemployment rate compounded by the absence of a reasonable expectation for even short-term economic progress. The weak, crumbled governments that remain are dependent on foreign intervention, charity aid, and disregard of past humanitarian crimes.

So what is the solution? The US, or any country for that matter, cannot easily invest in these countries or steer foreign aid to the people, as the Taliban, ISIS, or other militia groups will simply destroy what gets built or steal what is donated. Yet without solid infrastructure, there is no foundation on which to build profitable economies. Syria is a quagmire, the result of many actors both inside and outside its borders, but in Iraq and Afghanistan the US bears much responsibility for the chaos. America cannot morally or ethically wave “mission accomplished” banners and tell the people of these nations “good luck with the rest.” If the US did pull out of Iraq and Afghanistan entirely, the nations would passively pledge allegiance once again to ISIS and the Taliban, respectively, leaving the US with obvious national security threats.

Yet nation-building is a sisyphean task that has failed rather epically in Iraq. The US spent almost a decade propping up an Iraqi federalism, and then ISIS germinated and bombed the infrastructure we helped build, stole the government’s stabilizing oil money, and stockpiled the US-gifted military equipment when the police and military forces we trained and financed for years simply ran away or joined ISIS for a monthly paycheck. When ISIS is eventually degraded and forced out of of Iraq, the US is right back at square one where we were when we overthrew Saddam Hussein—except now Iraq is a much more wrecked country.

However, the biggest obstacle for Iraq and Syria is that their economies are, especially now, hopelessly dependent on oil (Afghanistan’s economy is hopelessly dependent on illicit opium exports). Oil happens to be an energy source much of the rest of the world is striving to abandon in order to preserve our planet from the wildly destructive consequences of climate change. As the price of oil goes down, these nations will be even less able to secure themselves without drastically redefining and restructuring their economies, which is of course difficult to pursue in times of sectarian civil war.

One hope for development and tackling the unemployment rate could be a giant influx of foreign direct investment into factories capable of cheap manufacturing industries, but this is of course only possible when Iraqi and Syrian cities are rebuilt or at least no longer being bombed daily. The ubiquitous threat of terrorism is not good for business prospects. Until then, who would want to take the risk investing in factory construction in northwestern Iraq? Though even if Iraq and Syria miraculously expel ISIS, they would likely revert to the same timeless ethnic and political struggles they faced prior to the war on terror, courtesy of past colonial foreign political absurdities.

A big wild card is of course the independent Kurdish territories in the northern regions of both countries, which have spent years now defending themselves and are committed to a self-sovereign Kurdistan of sorts. This is complicated because the US has spent the past few years giving the Kurdish militias a cornucopia of weapons and equipment to use against ISIS. Iraq and Syria are going to loathe any prospect of honoring Kurdish independence and the impressive loss of national territory a Kurdistan would mean, and for the sake of brevity let’s not even mention Turkey’s existential opposition to a Kurdish independence movement.

An apt metaphor for American involvement in these nations could be described as a game of terrorist whack-a-mole, and as it becomes increasingly easy to finance and arm terrorist groups, terrorism is not a waning threat around the world. Of course, it’s not like the US, Russia and Europe have shown any interest in ending the pursuit of military-industrial profits by selling guns, aircraft, and missiles to virtually anyone and everyone with the money and shell companies to buy them, which inevitably means that American weapons find their way to the very terror groups we are fighting. American profits are gluttonously feeding its own mole problem.

One solution, however unfortunate, is to prop up dictators willing to subject their people to cruelty in order to execute national stability (pun intended), but that is not without a historical abundance of negative consequences. Having a cruel, central and sovereign government might ultimately be better for these country’s people than having no central, sovereign government at all amid amid a wasteland of endless civil war, but the debate between promoting human rights and promoting ends-justify-the-means stability is hardly answered by propping up a despot.

Another solution could be to just abandon the Middle East, save only for sporadic aerial drone bombings and precision strikes when applicable, but what a cynical betrayal of the people we once promised security and even Americanesque liberal democracy. We left Vietnam and the Vietnamese are today an important US trading partner, but domestic communism is a pretty tame foreign political adversary compared to apocalyptic suicide bombers whose decades living through civil wars, endless bombings, and American occupations have given them nothing else to live for.

There is not a great solution to any of these quagmires, and I don’t propose one in this essay. It may be superfluous, but I’m merely diagnosing US foreign policy with a case of catch-22s, and unfortunately America has a president apparently unwilling to personally get involved. Donald Trump is too uneducated, uninterested, and unsuited to take responsibility for these impossible situations.

Remember when George Washington warned against foreign entanglements? Whoops.